“The pin” is one of the most powerful tactics you can have in your arsenal of attacks. No, I’m not talking about putting anyone’s shoulders on the ground and there are no 3-counts. Think of chess more as a war game than anything else… and “the pin” is when you’re attacking so heavily that a piece is “pinned down” and literally cannot move.

Pins can be performed on any piece, making it immobile out of the fear of having the king (or queen, or other higher cost piece) getting captured. It’s a very simple tactic, but a very strong one at the same time.

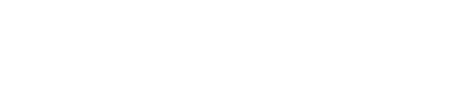

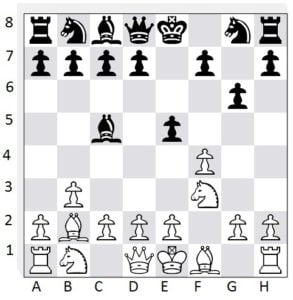

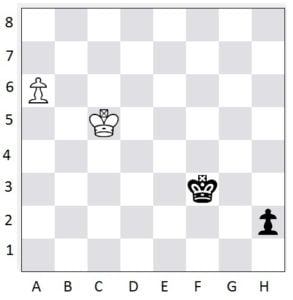

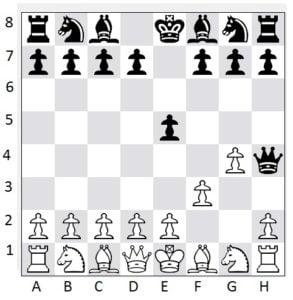

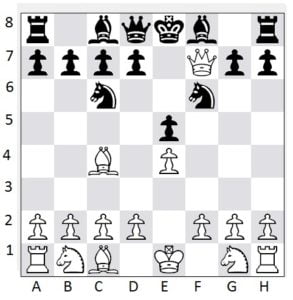

One of the most usual pins you’ll see is a bishop pinning a Knight. It happens very frequently in games, and in many openings you’ll see a position that looks something like this:

The knight can’t move because black would be putting himself in check by doing so. A normal response would be to push the A-pawn to cause the bishop to retreat. White can of course (and often does) take the knight forcing black to double up his pawns in the c-file, but not always.

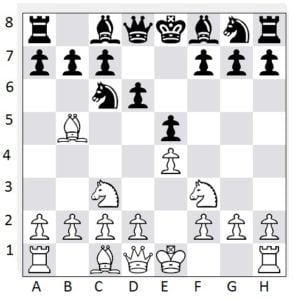

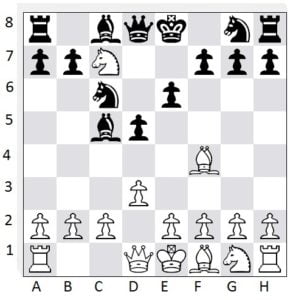

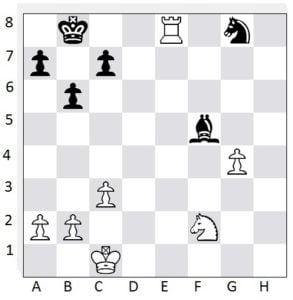

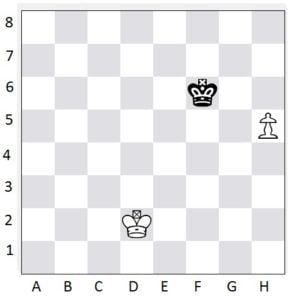

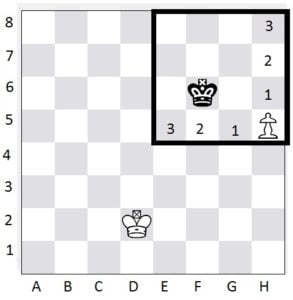

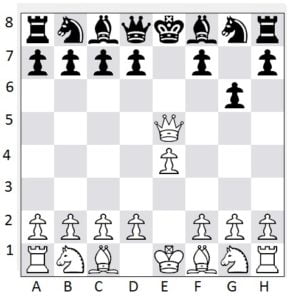

You’ll also, a lot of time, see a similar bishop-to-knight pin where the bishop will capture the queen if the knight is moved. This can be seen here:

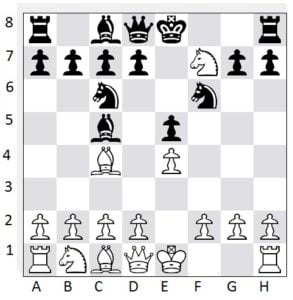

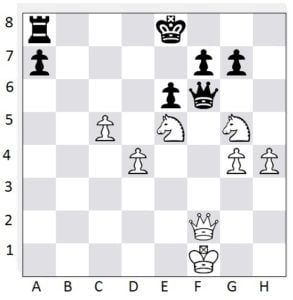

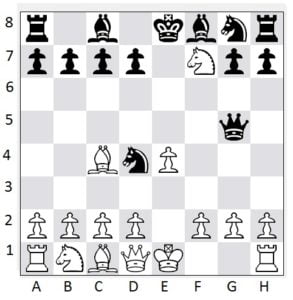

The Bishop, however is not the only piece that can create pins. Here are a few other powerful pin examples:

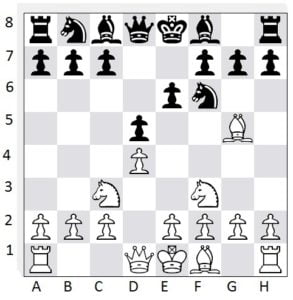

Here, white has black’s knight at F7 pinned… HOWEVER, black has a much more powerful pin. Black is checking white with the Knight at F2. White would LIKE to take the knight with his Rook, but the Rook is pinned in place by black’s Queen!

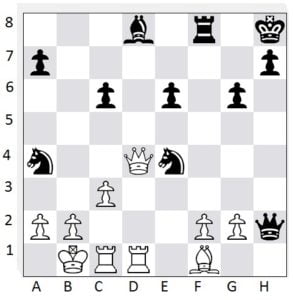

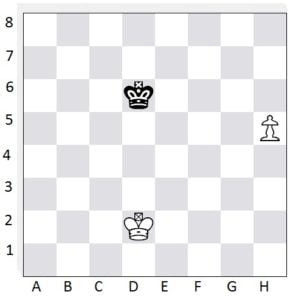

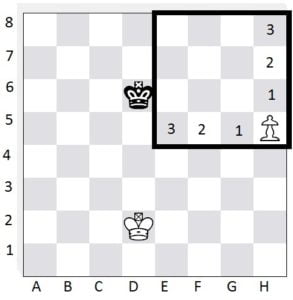

And can you see in this one that Black’s Queen is a gonner no matter what Black does?

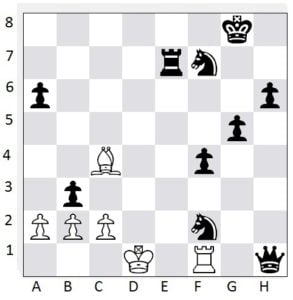

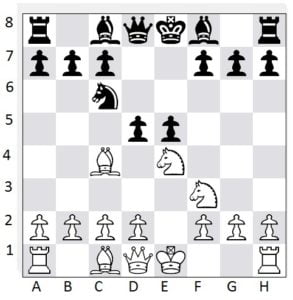

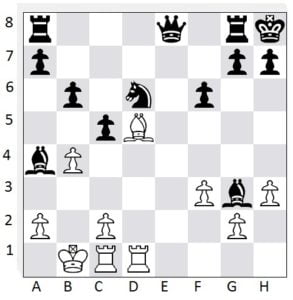

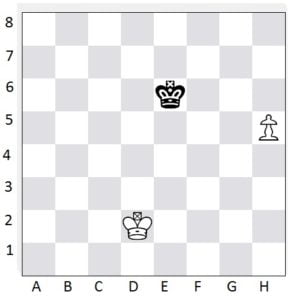

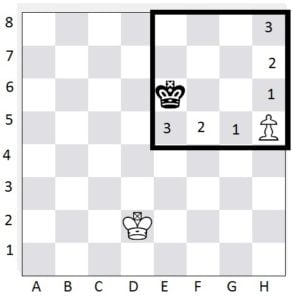

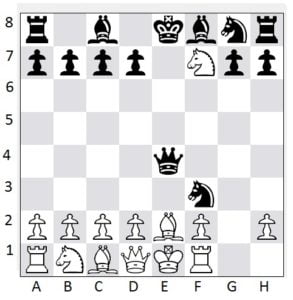

In these examples, the pin was due to a check that would occur if the piece moved. That’s not always the case. In this next example, a lesser piece is pinned because a more powerful piece would be taken, making the pinned piece an easy target:

Black would LIKE to either take the pawn at f4 or push to e4 to make White’s Knight retreat. If he does either of these moves, however, he will lose his Rook!

Pinning a piece down for threat of either a check or winning a larger piece is a good way to make your opponent’s troops immobile and in many cases win material. Be on the lookout for pin opportunities for both sides of the board. Yes, you want to try to pin down your opponent’s pieces, but remember, they want the same thing!