Josh from New Jersey asked me “Why is it that Pawns are allowed to move 2 spaces in the beginning?”

This is a great question on the history of chess, and so rather than writing a mini-blog to answer that question alone, I thought I’d go over several rules of chess that have changed over the centuries. Some of these changes include how various pieces move, the appearance of the chess board, and how to win a chess game.

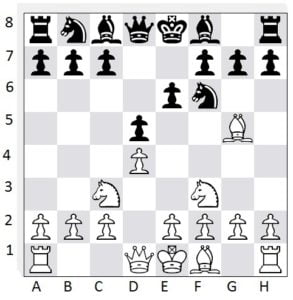

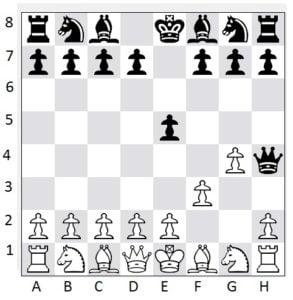

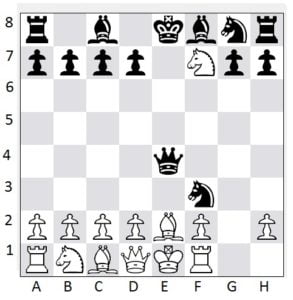

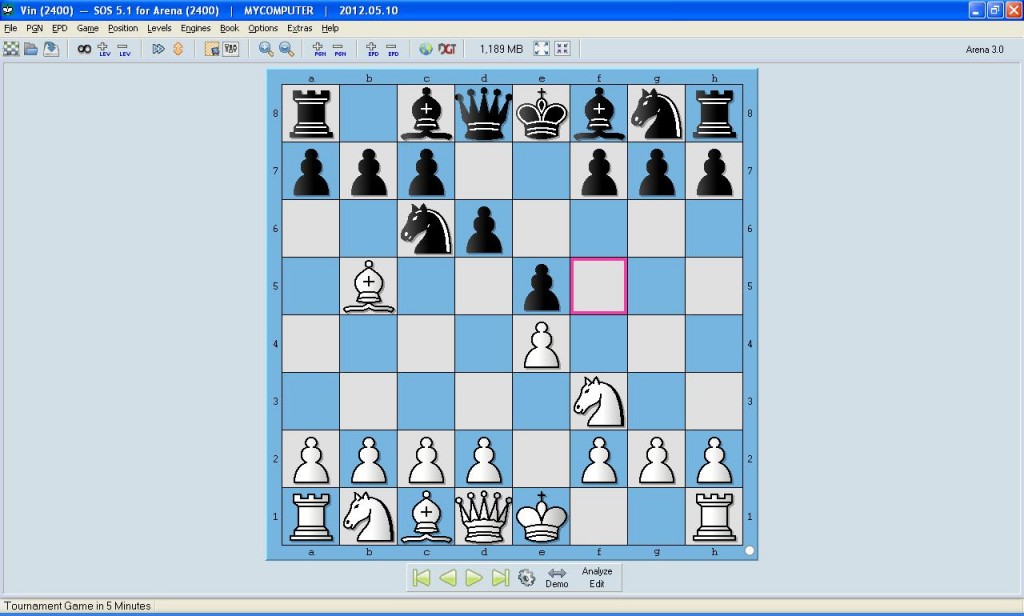

Pawn Movement

Originally, Pawns could only move forward one space at a time on every turn. Around the 1500’s, it was decided that the game of chess needed to be sped up and made more exciting. One of the things done to accomplish this was to allow the Pawn the option of moving up to 2 spaces on it’s first turn and therefore adding variety to the game (would the pawn move just one space or 2) and new strategies. When it became apparent that a player could use this rule to avoid capture (by moving the Pawn 2 spaces instead of 1 space in which it might get captured by a Pawn on the 5th rank), the rule for En Passant was added.

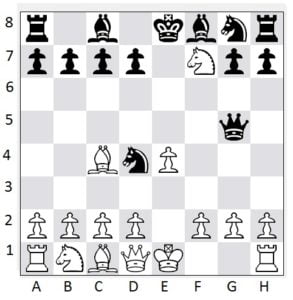

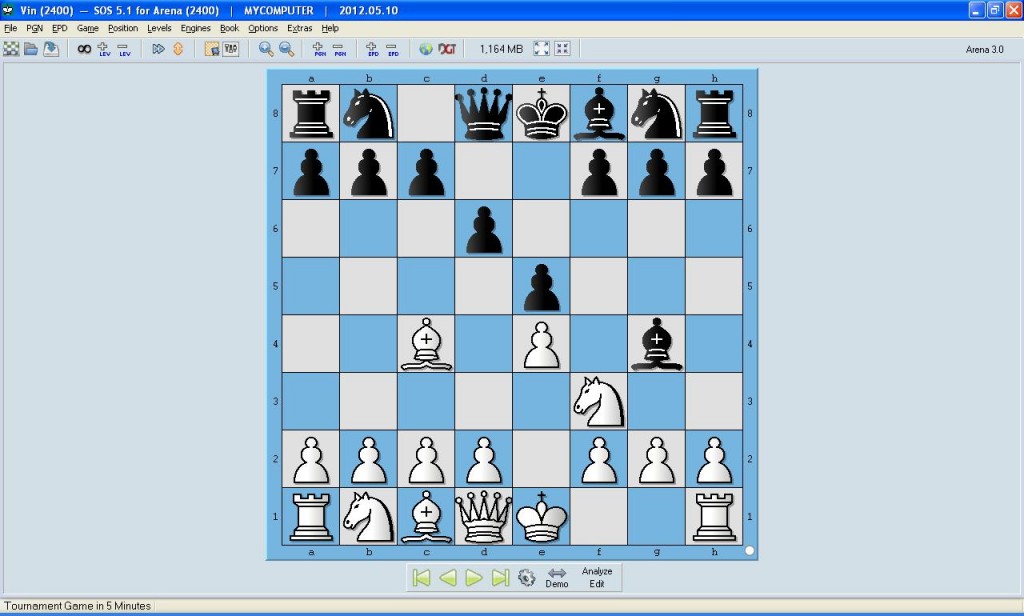

Pawn Promotion

Originally, Pawns did not promote when they reached the 8th rank, there merely could not move any more during the game. It wasn’t until the middle ages that it was decided to allow Pawns to be promoted to other pieces if they made it all the way across the board, but they could only turn into a Queen (which, at that time, was the weakest piece in the game). In the late 1400’s, when the Queen became a much more powerful piece, players were given the option of promoting their Pawns to any other piece. In the 1700’s, it was ruled that a Pawn could only be promoted to a piece that had already been captured (essentially putting a fallen piece piece back on the board in the Pawn’s place). This changed again in the 1800’s to it’s current form where a Pawn, when reaching the other side of the board, can be promoted to any piece, even one that has not been captured (essentially allowing a player to have multiple Queens on the board).

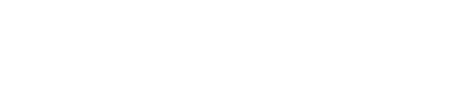

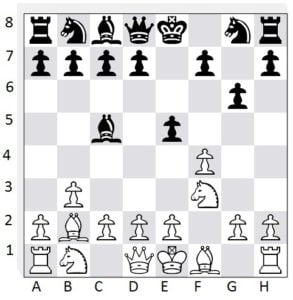

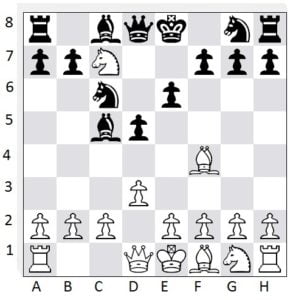

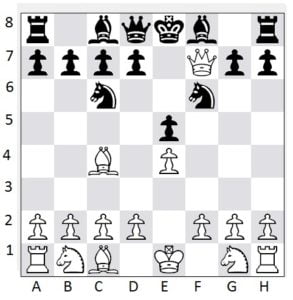

Bishops

Bishops have always been able to move diagonally. However to start with, a Bishop could only move up to 2 spaces at a time. Modern day chess has the Bishop moving diagonally as many spaces as it likes.

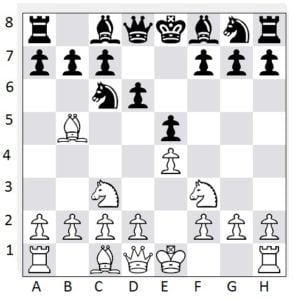

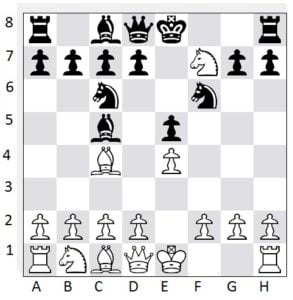

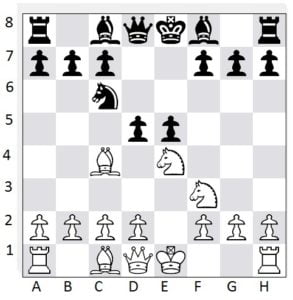

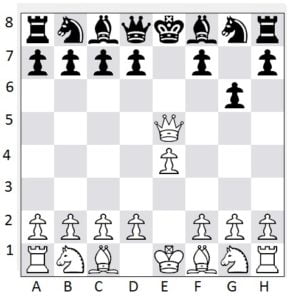

Queens

The Queen was originally the weakest piece on the board! The very first time it was moved it could be moved in any direction up to 2 spaces, but for every move after that it could only move diagonally 1 space at a time! It wasn’t until the late 1400’s that the Queen was increased to it’s current powerful status as a piece that can move any direction as many spaces as it likes.

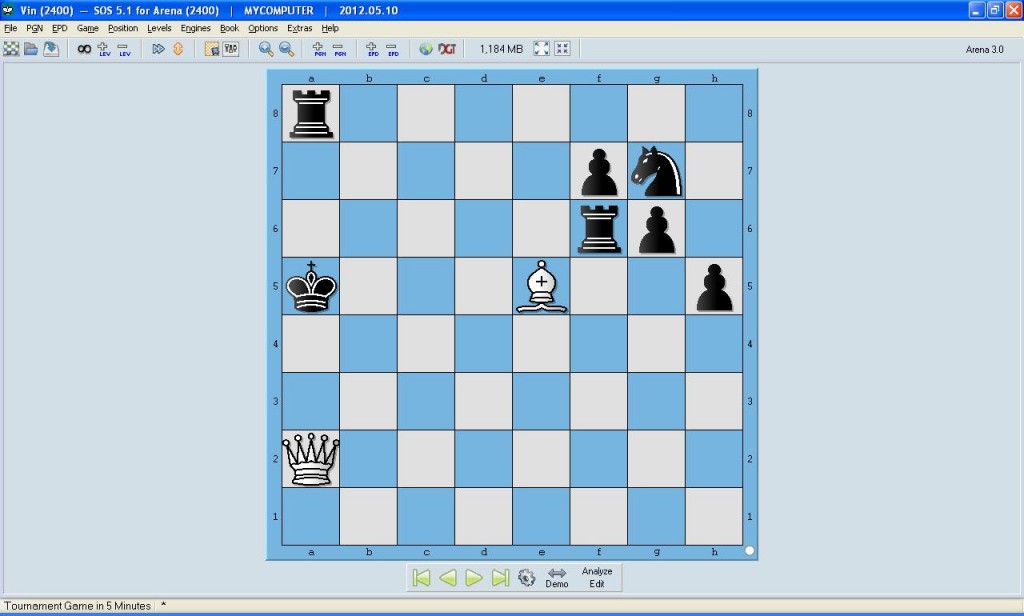

Stalemate

Stalemate has changed often throughout the history of chess. Up until the 15th century, a Stalemate was considered a win for the person that could force one to happen. Then, until the 16th century, it was considered an “inferior win”… it would still count as a win for the person who caused the Stalemate to happen, but in a tournament with money prizes they’d only be eligible for half the winnings. For a while (and in certain countries) a Stalemate was not allowed. If a player made a move that caused a Stalemate to occur, they were forced to take the move back and make a new move instead. In the 19th century, it was declared that a Stalemate should be treated as a draw, although to this day there are still many chess experts who believe it should once again be considered a win for whomever can force the stalemate to happen.

Checkmate

Up until the 1300’s, there were 3 ways to win a chess game: 1) Checkmate your opponent, 2) your opponent resigns, 3) capture all of your opponent’s pieces (minus the King). In the 1300’s, it was declared that taking all your opponent’s pieces no longer counted as a win, you had to Checkmate them.

Threefold Repetition

The threefold repetition rule (if the same position is repeated on 3 consecutive turns, the game is a draw) did not come about until the 1880’s.

The 50-move Rule

The 50-move Rule (if 50 moves are made without capturing any pieces or moving any pawns, the game is a draw) was introduced in 1561 by Ruy Lopez. In the 1600’s, Pietro Carrera said it should be 24 moves. In the 1800’s, Bourdonnais said it should be 60. For a while it was decided that all winnable endgames could be won in 50 moves or less, but then in the 20th century there were a few exceptions found. Because of these exceptions, for a while, it was declared you could have up to 100 moves in certain endgame situations. In 1989 that number was reduced to 75 moves, and in 2001 it was changed to 50 moves for all endgames, no matter the position.

Time Control

The first use of time control for games (which we’ll talk about in the next blog) was not introduced until the mid-1800’s.

White moves first

The rule that white moves first was not introduced until 1889.

My how things change!

Have a topic you’d like me to cover or a question you’d like to ask? send me an e-mail at [email protected]