Now that you know notation, we can start looking at some positions and games and analyzing, etc. In other words, now you can really start to learn to become a better chess player by reading books and blogs and solving puzzles, etc.

Let’s look at a few simple checkmates that are standard 1st time player mates to learn.

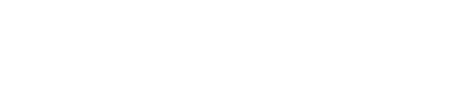

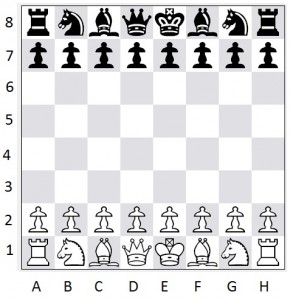

Fool’s Mate

This first simple mate (and actually entire GAME) we’re going to learn is titled “Fool’s Mate” because “only a fool would make such moves”! It is the fastest possible checkmate where the entire game lasts only TWO MOVES!

1. f3 e5; 2. g4 Qh4#

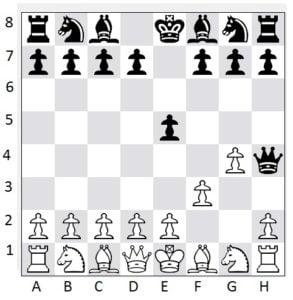

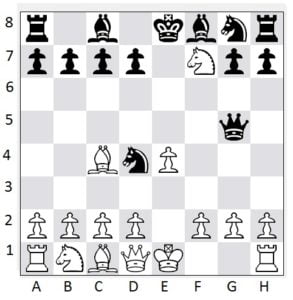

Scholar’s Mate

Scholar’s Mate gets attempted quite a lot in novice play and even some higher ranked players will go for it as a type of fear tactic, so it’s good to learn both what it is and how to stop it.

The moves for a Scholar’s Mate are: 1. e4 e5; 2. Qh5 Nc6; 3. Bc4 Nf6; 4. Qxf7#

There are a few variations of this from white’s side(such as bringing the Bishop out before the Queen, or bringing the Queen to f3 instead of h5), but that’s the basic idea. As black, there are many ways to guard against this particular mate.

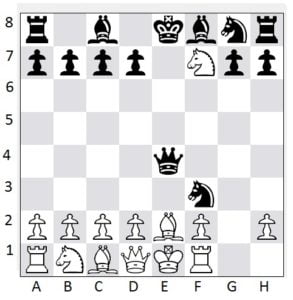

One way NOT to block is to threaten the Queen with g6. This results in a dangerous trap that allows White to check with the Queen (Qxe5+), forking the King and Rook:

You may think of answering 2. Qh5 with Nc6. This will still drop the e-pawn with check… not the worst thing in the world, but still not very ideal. 2. … Nc6 is still a good answer to block against the e-pawn capture. When White brings the Bishop to c4 for the threat of a mate, you can now push the g-pawn to stop the mate as the King/Rook fork is no longer an issue thanks to the e-pawn being protected by a knight.

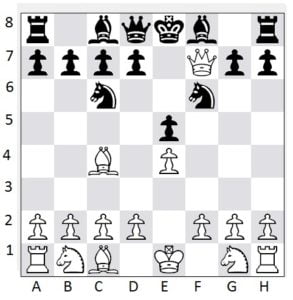

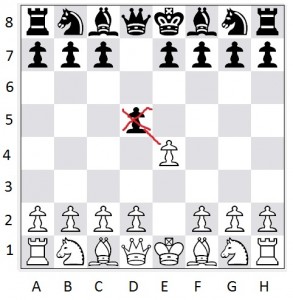

Quick Smothermate Trap

A Smothermate, as talked about in a previous blog, is when Checkmate with a Knight when the opponent’s King is blocked in by pieces (and can’t move) that can’t capture said Knight. Here is a cool little smothermate I saw recently that was very fast…

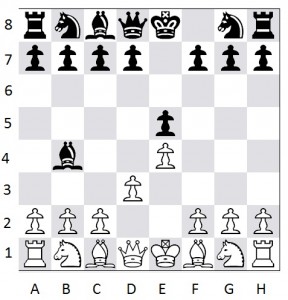

1. e4 e5; 2. Nf3 Nc6; 3. Bc4 Nd4; 4. Nxe5 Qg5; 5. Nxf7 (forking the Queen and Rook and can’t be captured by the King because it’s protected by a Bishop):

then black resumes- 5. … Qxg2; 6. Rf1 (so it doesn’t get taken) Qxe4+; 7. Be2 (moving the queen there would just result in a queen capture… which, given the circumstances might be the better idea for white at this point) Nf3#

These three fast mates are all possible (and infact, Scholar’s Mate happens quite frequently in beginning chess players’ games). Now that you know them, you can try them out on your friends, and protect against them when your friends try them on you!

Have a topic you’d like me to cover or a question you’d like to ask? send me an e-mail at [email protected]